Almost overnight, nature-based preschools have hit the mainstream.

And why not? The research says children who spend increased time outdoors develop stronger immune systems, more capable social skills, better sleep patterns—not to mention greater appreciation for and connection to the natural world.

So, whenever someone says to me, “We’re thinking of opening a nature-based preschool,” as a planning consultant, I respond, “Good idea!” But there is a difference between a good idea and a successful idea, and, when it comes to expensive ventures like preschools, a big part of that difference is a thoughtful business plan.

What is a Business Plan?

If you don’t come from a business background, you may know the business plan by another name: It’s the look before you leap; the ounce of prevention that is better than the pound of cure.

However you choose to think of it, a business plan is a document that spells out the goals and objectives of an enterprise, assesses its prospects for success, and describes the strategies for achieving it.

The end result of planning should be a business plan that provides staff and leadership with a road map that will guide the preschool in achieving its objectives. Whether for a new preschool or an existing one, a comprehensive business plan:

- Determines the preschool’s priorities relative to the organization’s mission, its resources, and its markets.

- Defines the programs and services it will provide to those markets.

- Describes the physical framework (i.e. the site and its indoor and/or outdoor spaces) needed to support those programs and services.

- Delineates how you will communicate and connect with the preschool’s markets.

- Describes how the preschool will operate.

- Predicts the costs involved.

- Lays out a plan for covering those costs.

- Proposes a delivery timeline.

A Philosophy of Planning

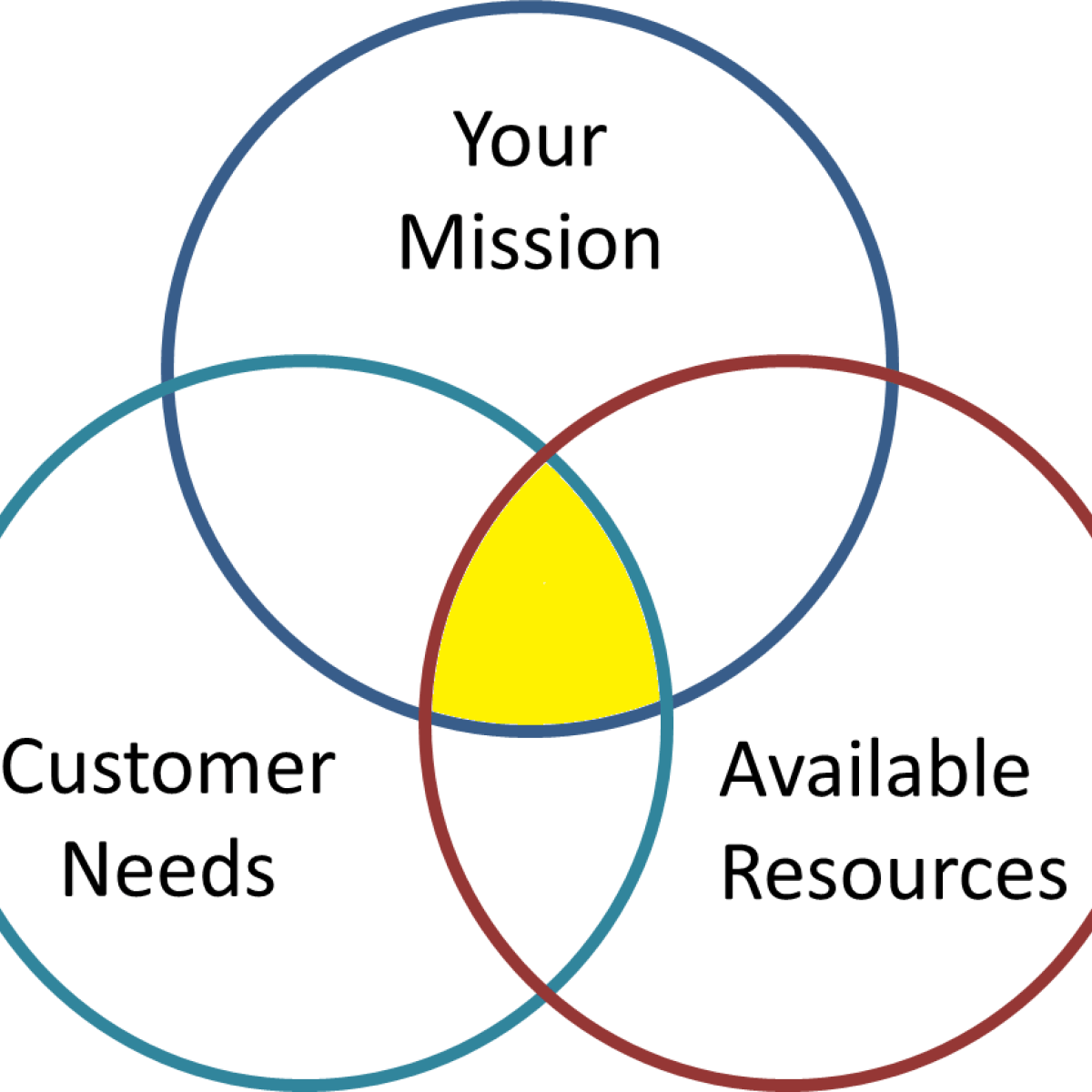

If all you needed to open a nature-based preschool was a patch of woods, a gifted teacher, and a group of eager children, the task would be challenging enough. In reality, it’s a lot more complicated than that. But the basic planning model is actually pretty simple. It looks like this:

Your mission is likely to be something you’ve already given at least some general thought to: You want to connect a new generation to nature. For the purposes of a business plan, though, you will need to be more specific. Is reaching low-income families especially important to you? Do you work for a nature center that wants the preschool to create an audience for family programs at the center? Do you need to be financially self-sustaining or even turn a profit? The answers to these questions and others like them are all a part of your mission.

Your available resources encompass all those external things that will support—or limit—what you can do. The most obvious are a site, skilled staff, and money. I include other limiting factors in this category, though—state and local regulations, the support of partners, the availability of public transportation near your location, the weather extremes of your site, and even your time.

Customer needs include lots of things that are obvious, as well as some you may not have thought about. Note that your customers are not only the children themselves, but their parents or other caregivers and (at least in some ways) their grandparents and siblings. And if you are a nonprofit with donors who invest in your work, they are “customers,” too.

The challenge facing you as you plan is that the three circles in the above model only partially overlap. Your customers have needs that may not be in your mission to serve—for instance, parents may want religious instruction for their children but yours is a secular organization. Or you will have resources that are irrelevant or even problematic—like active railroad tracks adjacent to your site. To be successful, you will need to come up with a plan that falls in the zone where all three circles overlap. It will need to achieve your mission, be supported by the resources you have (or can acquire), and meet the needs of the market you hope to serve.

So, the first thing you need to do as you plan a new nature-based preschool is gather a lot of information.

Just the Facts: A “Summary of Findings”

The first step in creating a business plan is to gather all the data that falls into the circles above and might have a bearing on the choices you’re about to make. Once you gather all that information, assemble it into one report that will be your “Summary of Findings.”

If you are associated with an existing organization—a nature center, a zoo, a school district, etc.—information about your mission will be easy enough to come by. It will be in your most recent strategic plan, perhaps supplemented by Board decisions, policy statements, or other documents. If you are starting a new entity, on the other hand, you get to invent all this from scratch!

You probably also have lots of information about your available resources already on hand. Some things will require research, however. Every project is influenced by a unique set of resource-related factors, but here are categories to keep in mind:

-

Site resources

(property size, natural features, local weather and climate issues, potential site hazards, ownership, current uses, access, availability of public transportation) - Building resources (sizes of existing rooms, availability of bathrooms and kitchen, disabled accessibility, utility costs, structural condition, potential hazards like asbestos and lead paint)

- Regulatory issues (zoning, state and/or local licensing requirements, building codes that will affect any required modifications)

- Human resources (staff and volunteer skill sets, certifications, time constraints, salary requirements)

- Partners (existing and potential)

- Financial considerations (health of the local economy, donor capacity and interest, potential grant sources, governmental tuition assistance programs)

Customer needs can be evaluated in a variety of ways. The process can be as expensive as hiring a consulting firm to do a market analysis, or as simple as researching community demographics, asking a lot of questions of potential clients, and studying other preschools in the area to learn how they are meeting local needs.

Once you have solid background information, you are ready to plan.

Big Decisions First

The biggest question, of course, is, “Can we do this?” If your answer is “Yes,” then a number of other big questions come thick and fast. Some examples of big questions:

- Will your organization operate the preschool, or find a partner to do it?

- Will the preschool be licensed?

- Will you offer half-day or full-day programs?

- Will you offer supplementary child care in the morning before school starts and in the afternoon after it ends?

- What market segment(s) will you target? How will that influence your tuition costs?

- If you need a building, will you use an existing space, modify one, or build something new?

- How many classes will you have?

- What student-to-teacher ratio will you strive for?

Smaller Decisions Next

Big decisions are usually made by more highly-placed decision-makers: Boards, department heads, executive directors, and the like. Smaller decisions are typically delegated further down the line. If you are working alone or in a small team, though, you’ll get to make them all—and there are many. Not every decision needs to be made as part of the business plan, however. The most vital ones to include in the plan are choices affecting the philosophy and finances.

Writing the Business Plan

Once you have made those decisions, write them down. There are a number of formats for business plans (just search the term on the Web). Here are plan elements I think are important:

- Key Decisions—These decisions guide the smaller decisions.

- Objectives—Specific, measurable, time-limited targets for what the preschool is to accomplish during its first three years of operation.

- Programming Plan—A summary of the activities that will be conducted at the preschool. These will include an overview of the educational curriculum, suggested family activities, and other functions. This section guides the preschool staff and its work.

- Site Program—A description of elements determined to be needed on the preschool site to accomplish the goals and objectives in the plan. These may include access routes, parking, outdoor lighting, trails, play areas, gardens, visual or aural screens, fences, structures, and similar. This is not meant to be a completed site plan; it is instead the information that will guide the landscape architect or other person who creates a final plan.

- Building Program—A description of the elements that will be needed in the preschool building, including the types of spaces it should contain, the number of people and/or types of functions those spaces will need to accommodate, and related information. For some projects, these will be modifications of an existing building. For others, it may be new construction.

- Marketing Plan—An overview of how the preschool will reach and engage its target markets.

- Operating Plan—Information about the operating hours, staffing, rules, regulations, and policies needed once the preschool is open.

- Financial Plan, Including Pro Forma Budgets (Capital and Operating)—An overview of how the preschool will earn and spend its funds from design and construction (if required) through the first three years of operations.

- Timetable—A target for developing and launching your preschool.

- Risk Analysis—An assessment of what could go wrong, along with ways to prevent those problems or to cope with them should they occur.

What You’ll End Up With

When you are finished writing your business plan, here is what you will have:

- A much clearer picture in your own mind of what this nature-based preschool will be and what it will take to create it.

- A document that will allow others to review and inspect your thinking, identifying its flaws and finding inspiration in its genius.

- A sales tool to use with supervisors, Board members, and prospective supporters.

- The investment and commitment of all the people who helped create the plan.

And you will also have a handbook to guide you through the next few years of hard work! Good luck to you!

About the Author

David Catlin has helped nature centers plan their futures—including the development of new nature-based preschools—for the past 17 years, most recently through David Catlin Consulting LLC. He lives in Springfield, Missouri, and can be reached through his website, www.davidcatlin.com.