Nature has a remarkable way of drawing out children’s individual traits. Children who are generally quiet inside the walls of a classroom will belt out in song in nature; children who feel confined by the small classroom setting will start to climb trees and take the time to show their peers how they can do it, too; and children who do not show much interest in the classroom reading center will find and discover letters as they explore the landscape. But how do we capture this learning as we explore alongside them? I have found that the richest forms of documentation come from the children themselves. Children are competent and able to learn to do their own deep documentation, and in this article I am going to focus on journaling as one strategy for tracking progress in children’s learning and development.

In the programs we run in the Presidio of San Francisco, we are lucky to be able to work with our children as they progress through the preschool years. Starting at age three, we begin to do bird-sits with the children, a technique that we have borrowed and adapted from Jon Young. We ask the children to close their eyes, “catch a bubble,” and try to listen to the sounds farthest away. Over time, we help them to focus on other senses, as well – what they can feel or smell while their eyes are closed. As teachers, we set the tone that this is a special time to calm our bodies and become observers. Eventually, as the children become confident in keeping their eyes closed to really hear the world around them, we add an extra minute at the end with eyes open to see any birds whose noises we might have heard. At the end of each bird-sit, we come together to tell the stories of what we have observed.

During these early years, the teachers capture the stories via notes or recordings so that we can build upon them with the children, check their recall of stories from the previous weeks, and help them to make predictions of what we might hear and see when we revisit particular places. Often the characters from these stories become important in our classroom setting, as well. We bring bits of our time in nature back to the classroom in the form of photographs, storytelling, and video recordings for further exploration.

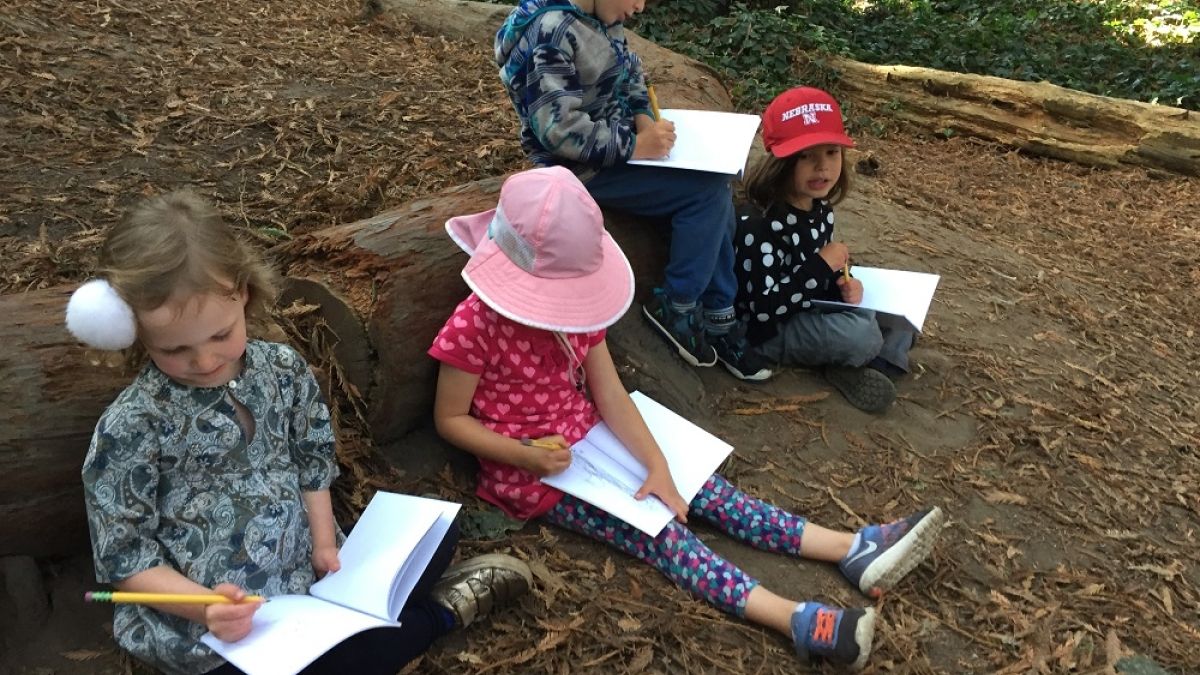

Image credit: Stretch the Imagination

We spend a great deal of time building these observational skills with our children so that by their later fours and fives they are ready for nature journals. Our oldest children begin their year by being introduced to their own nature journals. We explain to them that the journal is a special place to document something from our bird-sit or from our day together in nature. As teachers, we want to model that this is not a free-choice writing space, but rather a way to document with a particular purpose. These pages then become a wonderful piece of documentation that captures how children are developing their writing and fine motor skills as well as how they are connecting with the natural world around them.

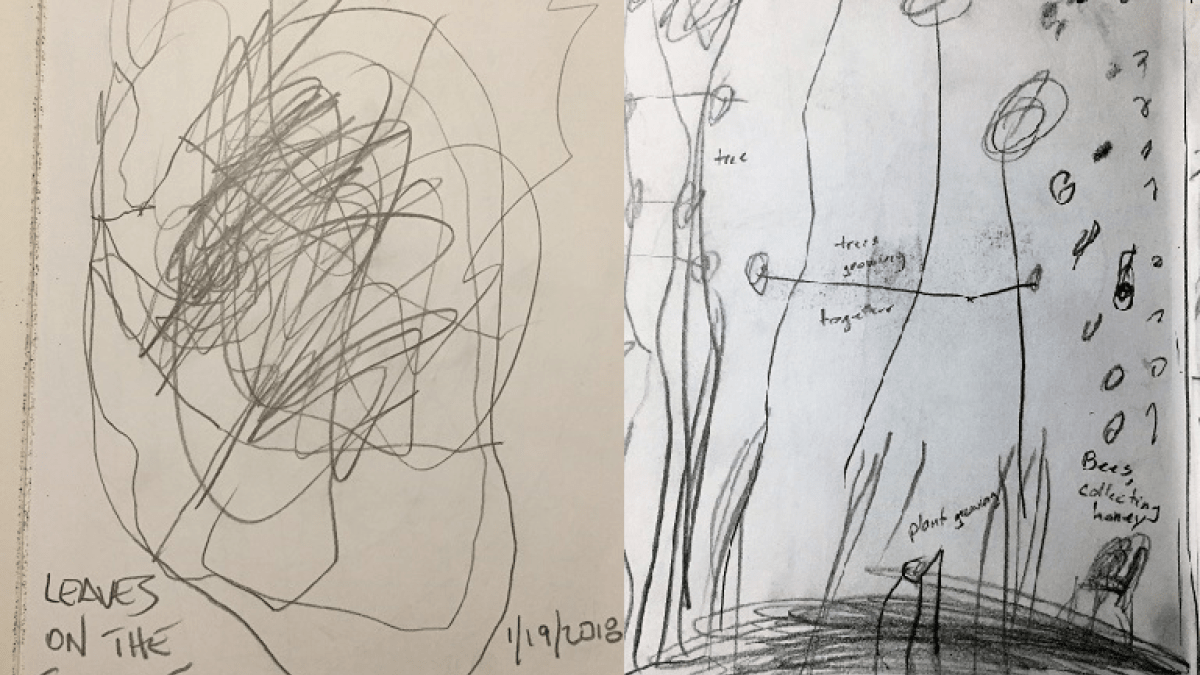

Children’s range for representational drawing is vast. Personal journals allow us to meet the children where they are in their individual development. We are able to capture each child’s unique symbolic expression every time they journal, showing them that their drawings and stories have value. This also gives us a deeper picture of their growth over time. For example, one child grew from creating large fast swirls to represent anything from people to leaves to drawing straight lines with detailed limbs for trees. This child was always attracted to trees and the moss that grew on them, and so it makes sense that trees would be one of his first steps toward clear representational drawing.

Representational drawings by the same student, one month apart. Image credit: Stretch the Imagination

Once we have laid the foundation for this kind of documentation, children will often request their journals when we are out exploring or they will ask a teacher to take a picture of something so that they can document it later. This year, a new student joined our group and he was not used to expressing himself with paper and pencil. For the first several weeks, he made quick journaling marks, expressed what they were, and moved on. However, coming into a world of documenters, he began to notice the value of this work. Soon, he was filling up an entire page and asking if he could go back and document on a second page, as well. He exudes such pride when he shares the images he has drawn in his journal of himself climbing a log or the loud bird that flew over us during our bird-sit!

The children’s natural classroom journals are a big piece of our parent conferences. They capture so well who the children are, what they value, and where they are developmentally. Parents often come away from these conferences wanting to get journals for their children so that they can use them in other spaces, too. While it takes time to develop the observational skills to get these rich pieces of documentation, I am confident that by setting a tone of valuing documentation, giving individual attention to children’s work, and placing value on their words and stories, journaling can help us to document a big part of the learning that takes place in nature-based early childhood education settings.

About the Author

Tracy Neal is a Red Oaks Teacher at Stretch the Imagination in San Francisco, CA, and has a Master degree in Early Childhood Education from Mills College.

Delve Deeper

Curious how other early childhood environmental educators document learning in their programs? Watch this free webinar organized by the Natural Start Alliance and the Northern Illinois Nature Preschools Association on Tools and Tricks for Nature-Based Documentation and Assessment.