If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.

-Rachel Carson

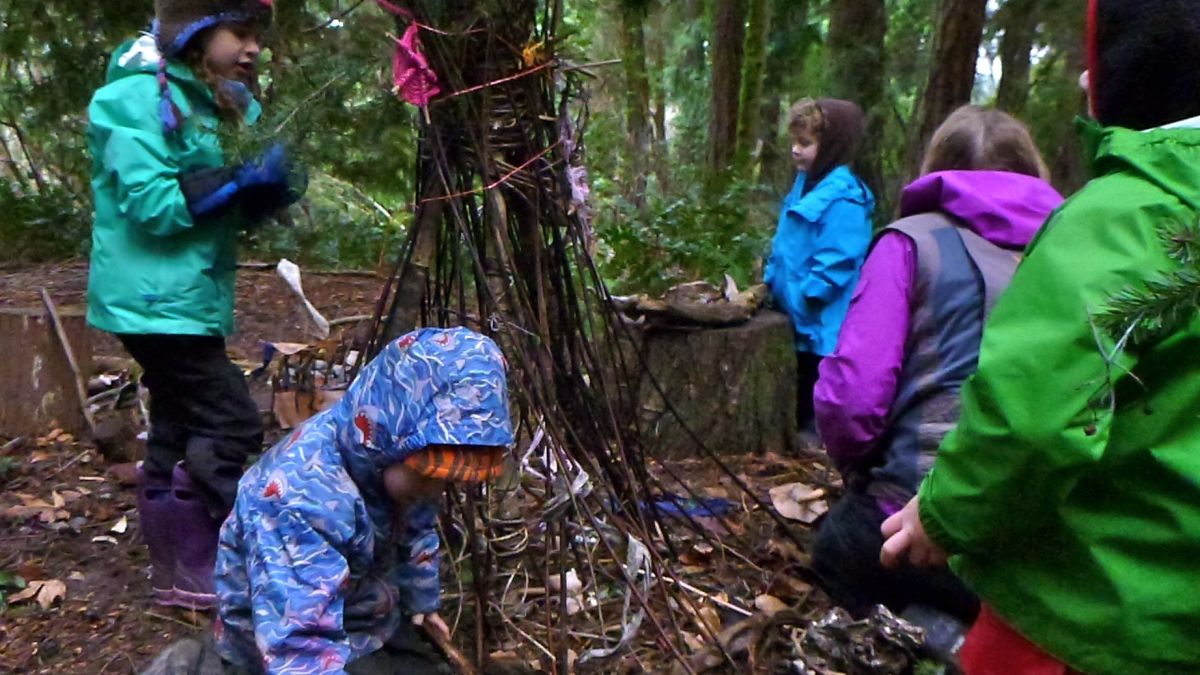

Atop a hill at the center of our outdoor classroom at the Fiddleheads Forest School in Seattle, Washington, is a sprawling fairy village. Scramble up a looping pathway past a few western red cedars and a bed of native Mahonia and evergreen elderberry and you’re there. It’s a little metropolis, complete with gardens, a town circle (much better than a square, according to the students), a movie theater/restaurant (depending on who’s giving the tour), and even a towering “Space Needle” in honor of our city’s most prominent landmark. The place grows and changes with each passing week. Children collect items from the surrounding area and put them carefully and purposefully around the village. The fairy village has been central to the life of our classroom since it came into existence, and the educational opportunities it affords the children make it worth exploring.

Imaginative Play and Possibility

Kit Harrington

There is an air of enormous possibility that surrounds the fairy village at our school. According to Tracy Kane, the author of a number of wonderful fairy house books including the laminated, weatherproof one we keep in our classroom, it is the “allure of nature’s enchantment” that can “spark our creativity and nourish our imaginations.” Students comb the grounds looking for signs that the fairies have been there; a displaced shell or a previously undiscovered stone is often enough to send them into a frenzy of discussion and activity: “The fairies came! The fairies came!” reverberates throughout the classroom until the students are all drawn up to the village. They gather together, positively vibrating with excitement, and get right to work assigning tasks: “Okay, Colin and I are going to make more things for the fairies. Charley, do you want to write the letter to them? Who can help Mason dig the hole for the ocean? Let’s see, oh look—that’s a great stick to use! It’s a great stick, the fairies will love it.”

Sarah Heller

I believe the simple joy derived from magical experiences can be traced to the idea that anything is possible. From the perspective of the children, there is a sense that if tiny creatures might arrive and use their magic to effect change on the world, then who knows what other surprises each day has in store? Children want to believe because the act of believing itself is exciting; it offers enormous opportunity for learning and play.

But whether or not the children believe in fairies is often unimportant. Once they have encountered something that is potentially magical, the role the students embody in their imaginative play becomes that of an individual who believes in fairies and is attending to their happiness. Discussions about the existence of fairies can wait for another time, because the game is afoot.

The Child’s Domain: Self-Directed Skill Building

So much of the world is off-limits to children, but the fairy village is their domain. Annie Quest, a social pragmatics teacher who spent years running fairy camps in the green mountains of Vermont, explained the attraction for her as a child: “I felt small, [and] fairies are small, but they’re very powerful. They’re much tinier than people, but they can turn anything in nature into things that are useful for themselves.” In some ways, the most magical element of the fairy village is its ability to give children the sort of control over a whole world that they so often struggle to achieve in their own lives. In the land of fairies, only the children decide when it is bedtime.

Kit Harrington

Embedded in the act of creation is consideration of the needs and wants of others. The children practice empathy through experiencing caring for this imagined other; it gives substance and purposefulness to their work. “Here, these shells can be a table so they will have a place to eat, and okay, now there is a table so it needs plates, and here these little hemlock cones will be the food—now how are we going to build chairs for them to sit on?” The number and variety of things that need attending to stretches infinitely into the imagination: tiny cradles for baby fairies need blankets to keep the infants warm, roofs are required to protect the inhabitants from wind and rain, new fairies must be built from sticks and cloth so that the others will have friends, even the problem of electricity must be addressed!

The precision required to build these little homes encourages concentration and fine motor development. Because the work is creative and self-directed, the children are likely to engage far longer than they might with a traditional fine motor work. The author Tracy Kane echoed this in her own experience, remembering how “One boy brushed his dog for a week to create a soft floor for the fairies.” Activities such as scooping, pinching, threading, weaving, and tying are inherently a part of construction, and as the children’s skills are refined, so are the finished products that they create.

Over the past two years, the fairy village at our school has mirrored the development of the children around it, transforming from a pile of objects that the children gathered from around the classroom into a true “village” in which the residents are constructed from twigs, twine, and small bits of cloth. For the 3-year-old child, a finished product may look more like a pile of sticks to the untrained eye, whereas an older student of 4 or 5 will regularly take on a more elaborate design, knotting twine and weaving bark through posts for walls. Often the older students will support the younger ones, perhaps by demonstrating how to twist a stick like a drill to get it into the ground properly or helping to dig around a particularly difficult rock.

Sharing Spaces and Negotiating Differences: Science and Belief

The fairy village is a shared space. The children must negotiate the space with one-another, and understand that other children may differ in the ways they want to use that space. The disagreements that inevitably arise from working together in a small area offer opportunities for the children to practice conflict resolution. They learn that, to enjoy the fairy village, they must be flexible and they must share their ideas and plans with the others who are working with them, and they come to terms with the fact that weather can sometimes create more havoc than an uninformed peer.

“Are fairies real?” is a common question in the forest grove, and more than just encouraging imaginative play, it has provided the children with a basis for using scientific principles to develop hypotheses, gather evidence, and arrive at conclusions. In small groups, the children enjoy discussing their opinions, and these conversations provide an opportunity to practice listening to and respecting different perspectives.

Too often in early childhood education, we feel compelled to moderate or inhibit debate among young children, but in my experience, I have discovered that it is impossible to teach conflict resolution without allowing students to practice differences of opinion. When children freely express their own ideas and are encouraged consideration of other’s, they develop a sense of self while simultaneously building empathy. Whether or not they “believe,” the process of searching for, discussing, and constructing elaborate new dwellings for these imaginary creatures wherever we go is enthralling. It is the shared journey, the tiny discoveries, and the potential of the unknown that lie at the heart of this experience and make it so compelling. As Quest put it, “If you believe in fairies they are real. If you don’t believe in fairies they are real fun.”

Loose Parts and Construction

Anything in nature can become a part of a fairy village, and from an educational standpoint, this is part of the allure. As Kane explained to me, “Fairy houses get children outside looking at natural materials in new ways. Sticks and bark become walls and roofs. Stones make strong foundations and acorn caps are a perfect size for dishes.” There is enormous cognitive benefit to allowing children to imagine how the natural elements around them might fit into their creation.

Kit Harrington

A good fairy village must have plenty of materials available for construction. In developing our school’s fairy village, my co-director Sarah Heller and I took instruction from Simon Nicholson’s theory of loose parts, the idea that “In any environment, both the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery, are directly proportional to the number and kind of variables in it.”

With that in mind, we collect objects from the surrounding environment including stones, sticks, and fallen moss or lichen from trees (we teach the children to only collect items that have naturally fallen on the ground so as not to disturb the surrounding ecosystem) and combine them with driftwood, pebbles, and seashells combed from the nearby Puget Sound. Stumps and tree circles provide platforms for display.

Kit Harrington

Sandy Tanck, who led the design of the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum’s inspiring natural play gardens, suggests a similar approach: “We create simple, sturdy forms that kindle imagination and suggest possibilities: fort-building frames, a throne-like stump, a ‘stage’ with log seat for the ‘audience,’ a log table and shelf. Alongside these we offer supplies of sticks, cones, branch slices, burlaps, and other ‘nature bits.’” These materials are readily accessible in almost any outdoor environment, and take only time and attentiveness to procure.

If you search online for fairy villages, you can easily find intricately detailed—and sometimes exorbitantly priced—fairy sculptures for sale. But these objects each have a specific purpose, and most are not meant for handling by tiny fingers. Cognitively, the potential of dynamic, open-ended materials like those found in nature far outpace those of the store- or Etsy-bought kind.

Of course it’s difficult to resist the desire to provide the children with beautiful, complete forms. Whenever I am tempted to do so, I try to remind myself of something that Tanck expressed during a panel on nature play, the lesson she said took the longest to sink in: “If everything about the features we provide is already ‘done,’ there's nothing left for children to do but destroy it.” In contrast, she and her team discovered that, “When a feature looks started yet unfinished, it becomes an open-ended invitation for creativity, imagination and productive energy to flow. The results are magic to watch.” So often in preschool, I find that my most important role is to know when to get out of the way, and the fairy village offers a perfect opportunity to simply sit back and observe.

Back at Fiddleheads, the students are contending with changes to a fairy farmer’s market they constructed the month before at a nearby nurse log. “Somebody knocked it over,” remarks a student. “Or else a squirrel wanted to get the seeds to give to its babies?” suggests another. “Maybe it was the fairies!” cries a third. There is a pause as they consider the options in front of them. “Well,” one of the older children points out, “the fairies are going to need more food. We have to get everything for them!” Within minutes they’ve scattered, darting down the hill, pausing here and there to collect a lawn flower or hemlock cone. The children are focused, they have purpose, and they are absolutely full of joy. This task, in this moment, is as important as anything they can imagine, and the possibilities are endless.

About the Author

Kit Harrington is the co-director of Fiddleheads Forest School at the University of Washington Botanic Gardens in Seattle, Washington. In addition to her administrative capacity, Kit lead teaches and develops curriculum and school philosophy. She will be presenting a workshop on teaching flexible thinking and self-regulation in the outdoor classroom at the Nature-Based Preschool National Conference in Elachee, Georgia, in August.

Resources for Further Exploration

Fairy Houses, Tracy Kane

A story about a little girl who builds a fairy house on an island in Maine. Reinforces care for the environment, use of natural materials and nature connection.

Fairy Houses…Unbelievable!, Tracy Kane and Barry Kane

Gorgeous photographs of fairy houses. We laminated a copy and the children use it for inspiration, rain or shine.

How to Find Flower Fairies, Cicely May Barker

A beautiful, intricate pop-up book. We love the creative way the authors use the pop-up book format to encourage children to peer into, under, and around objects in their environment.

The Giant Golden Book of Elves and Fairies, Jane Werner and Garth Williams

Annie Quest’s favorite childhood fairy book.

If You See a Fairy Ring: A Rich Treasury of Classic Fairy Poems, Susanna Lockheart

Combines the poetry of Robert Graves and Laura Ingalls Wilder with skillfully rendered illustrations that change as readers turn the page.

On the Web

- Creating a place for Nature Play

- Let the Children Play Theory of Loose Parts

- Nature Play at Home

- Fairies at Nature Preschool

- Fairy Fun – 40+ fantastic fairy ideas